What are today’s most scarce resources?

While money can be found, borrowed, printed or even invented, we all know that no amount of money can buy a 25th hour in the day. Time is limited, tomorrow is not guaranteed. And no amount of money can make someone really care. No amount of money can motivate someone to give every ounce of their energy and talent. You can’t buy real enthusiasm! The only way to get the best work from someone is to inspire them and then get out of their way.

For most companies, the most scarce resources are the time, energy and talent of their people, and the insights, ideas and wisdom those people generate. As Michael Mankins and Eric Garton write in Time, Talent, Energy:

““Ideas don’t just materialize; they are the product of individuals and teams who have the time to work productively, who have the skills they need to make a difference, and who bring creativity and enthusiasm to their jobs…what separates the best from the rest is leaders’ ability to manage human capital in the broadest sense.””

It can feel like we never have enough time. Our energy doesn’t feel unlimited. And world-class talent is hard to find and afford. But without these three elements, time, energy and talent, it’s nearly impossible for innovation-and-profit-driving ideas to be uncovered, refined, and brought to life.

Step Zero: Start with yourself

As a leader of people, it's your job to unlock and maximize the energy and talent of your team by helping them use their time well. While it’s tempting to start with your team, I recommend starting with yourself: be the change! Start by using your own time, energy and talent well. Then, coach your team to do it, too. Leaders can do this by:

Modeling the intentional use of time - by focusing on the important over the urgent (bullet point #4 below)

Modeling the intentional use of talent- by focusing ONLY on things that are great uses of your unique skills, your Zone of Genius (bullet point #3 below)

Once you start intentionally focusing your time and talent, and coaching and encouraging your team to do the same, the creative energy in your organization will start to be unleashed on an individual basis. But to scale your team’s impact, you need to have the facilitation skills to ensure that the meetings you host don’t waste anyone’s time or suck anyone’s energy. This is the magic key to unleashing the time, energy and talent of your team: creating moments of impact with your team by bringing folks together to solve problems in effective ways that wouldn’t have happened without that meeting. Without the key ingredient of Facilitative Leadership your meetings will waste your team's resources, rather than unleashing them.

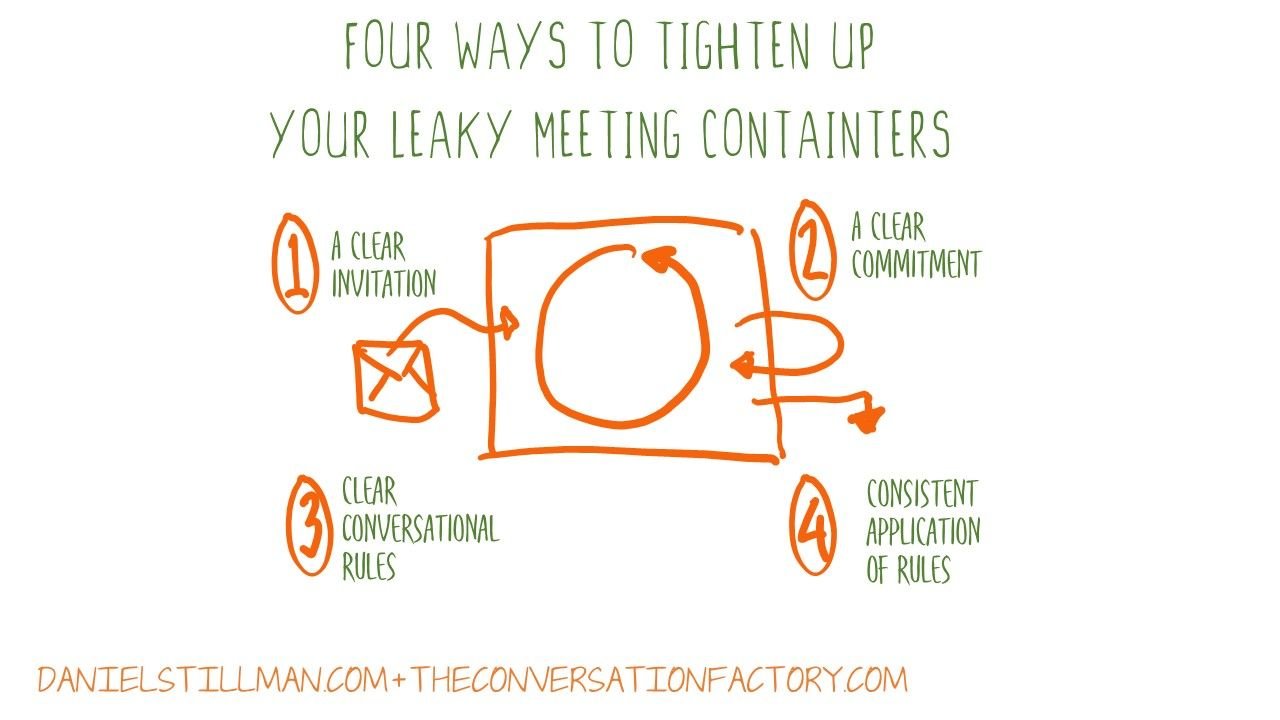

Facilitative Leadership is rare, but leaders who master it can intentionally create spaces and places where people are empowered to do the best work of their lives. It’s a topic too big for this essay. But you can read more about Facilitative Leadership skills like mastering turn taking, asking powerful questions, the 5Es of meeting experience design and even leading silent meetings at the links embedded here. You might even need to lead a meeting about meetings with your team or work to make your meetings less “leaky".

There’s another way to describe the outcome of this approach, the real goal: creating a platform for human flourishing. (Those words are from Ashley Goodall, former Cisco Exec and currently a leadership expert and author of the Bestselling books, Nine Lies about Work and The Problem with Change, AND a wonderful guest on my podcast.)

1. Ask for their best and create a platform for human flourishing

I love this phrase, “a platform for human flourishing”.

It’s a reminder that the real job of a company is not *just* to maximize shareholder value, which it must do - that’s table stakes! A company exists to serve a customer, to make their lives better. But that’s just one side of the platform. On the other side are all the people who come together to make that happen. Employees are customers of another sort, and creating a place to work that’s a drag for employees while creating value for your external customers is not just a missed opportunity, it's unsustainable.

Recently, a coaching client of mine complained about the quality of work coming from their team. They wanted to communicate clearly what the “minimum standard” looked like—and make it crystal clear that nothing should get out the door without meeting that standard.

I pushed back with a question:

“Are you trying to create a minimum standard company? A minimum standard culture? Or do you want a company where people know they have an opportunity to do the best work of their lives?”

“The best work of their lives?!” my client asked.

I asked them—and I’ll ask you to consider this as well—when were you first on a team where everything hummed? A place where you look back and think, “Wow, we did some great stuff”? A place where you were proud of the output, even though it was a lot of work? And that you still feel pride about?

Now, think about the team you lead today. What are you inviting them to do? Just “good” work? Or work that they will continue to be proud of in 10 years? As a leader, you can create that opportunity. Setting the expectation that people can do “the best work of their lives” under your leadership is a bar that people can be excited to meet. And when your talented team members are excited about their work, you’ll get the best energy and application of talent from the time they spend.

2. Architect moments of efficient collaboration through Facilitative Leadership.

Remember the quote from Mankins and Garton that we started with:

““Ideas don’t just materialize; they are the product of individuals and teams who have the time to work productively””

That work never happens 100% alone - we have to come together to talk, to coordinate, to collaborate. And… We’ve all been in meetings that intend to help us do just that, but instead waste people’s time by not delivering on real value. It’s exhausting for everyone. In fact, it’s a real drag.

The more intentional you can be about the time your team spends together, the higher the chances are that you will get the most out of that time. Intentionally designing the time people spend together is the heart of Facilitative Leadership. In order to unleash the time and talent of your organization, you need to be able to facilitate these moments of impact. Otherwise, you create what Mankins and Garton call "Organizational Drag”: friction that drains people’s energy and wastes people’s time.

Many organizations, even at small sizes, create organizational drag. For example, one founder I worked with had a senior team of only five people, plus another 15 or so in the rest of the org. They were very early in their product-market fit iteration, but challenges were already emerging from the way they ran leadership team meetings. When I hosted 360-degree review interviews with the leadership team, I heard again and again that they felt several of their meetings duplicated or overlapped efforts and that they didn’t feel that their time was being well spent. Many of the team members also commented in the interviews that the CEO took up the most airtime in the meetings. While it was critical to the team that the CEO share what they felt were the biggest challenges facing the young company, the C-suite wanted the opportunity to contribute more, not just listen to the CEO.

Facilitative leadership creates opportunities to unleash the energy and talent of your team, and this is a mindset and skillset I had to start coaching this leader on - how to make sure they were making sure the entire leadership team felt like they were contributing their time, energy and talent in every meeting.

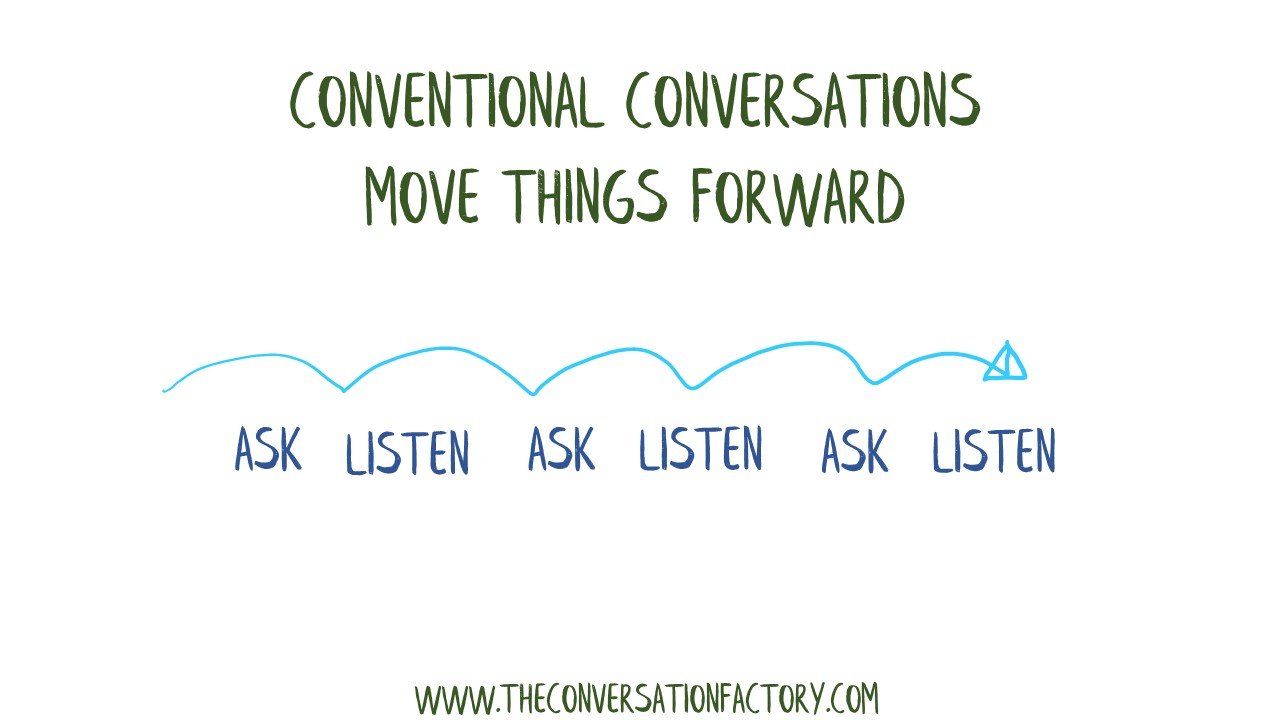

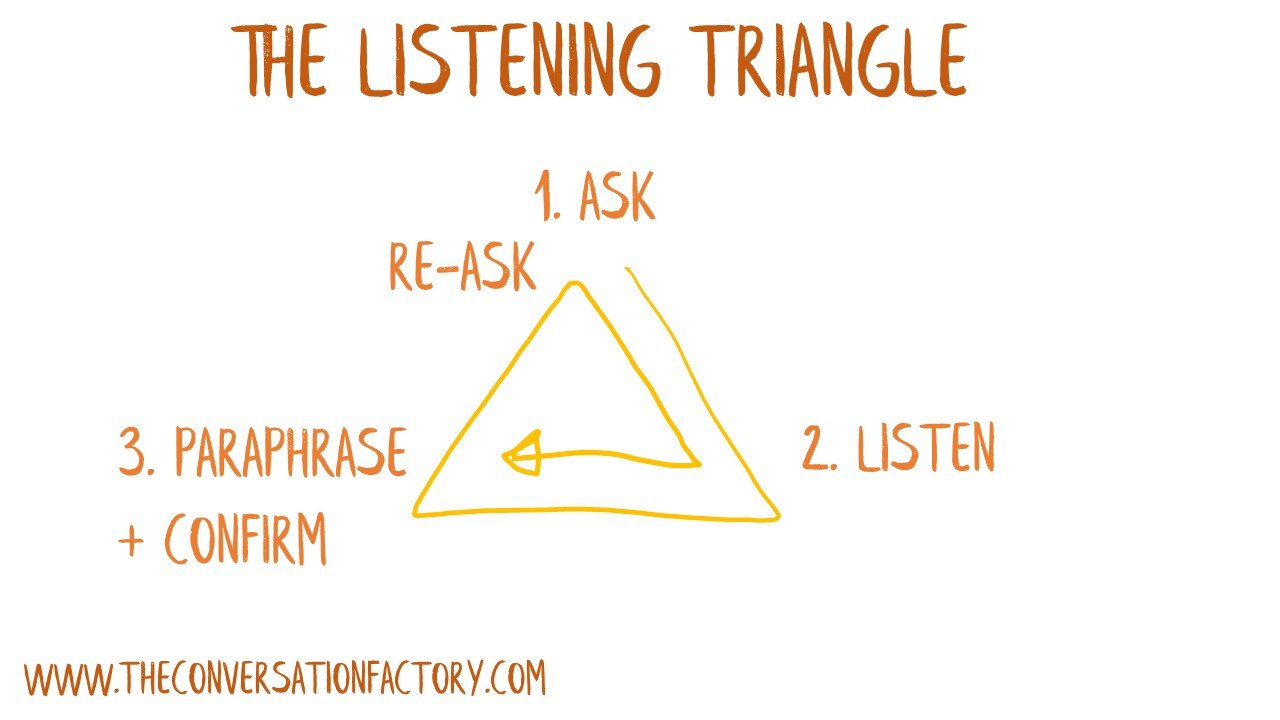

Every meeting is a potential moment of impact. In our podcast conversation, Lisa Kay Solomon and Chris Ertel, co-authors of Moments of Impact, made this idea clear: “At these critical moments, everyone will be looking at you—not for all the answers, but to help them unearth the answers together.”

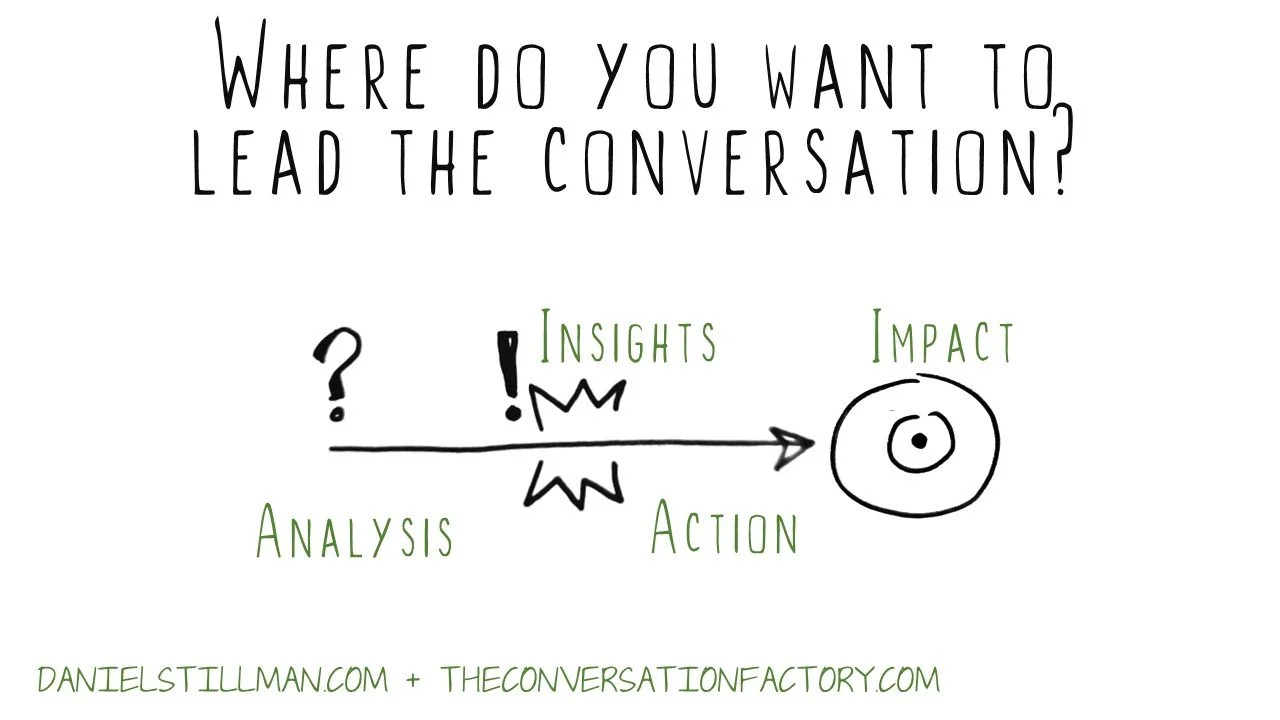

Solomon pointed out that what she and I call “Conversation Design” is one of the most impactful leadership skills—and one of the hardest to teach. The ability to architect efficient, collaborative conversations is an impact-multiplier skill, because doing so enables people to leave meetings with a sense of momentum rather than feeling like it could have been an email. Refreshing your facilitative skills is one way to make sure you're creating opportunities for your team’s best work to be unleashed and connecting their diverse talents to drive creative thinking.

In Solomon’s definition, the basics of facilitation are simply about the non-negotiable, essential mechanics of leading a conversation, like starting and ending on time and being able to run different modalities of participation effectively. Conversation Design is about the questions leaders need to ask themselves in shaping strategic conversations to make sure they don’t run efficient but ineffective gatherings.

Questions leaders can ask themselves before hosting a meeting

(after asking the all-important question, is this meeting necessary?):

"What do I want this conversation to advance?"

"What do I want people to know, feel and do long after this conversation?"

"What is the culture I want to build by the choices that I make in this session?"

How will this gathering unlock the time, energy and talent of my team?!

3. Optimize time and talent. More Energy follows.

Physics teaches us that Energy can’t be created or destroyed - we can only use one type of energy to create another. Like how our bodies change the chemical energy in the food we eat into mechanical energy when we move things around. Or when a roller coaster’s potential energy at the top of a hill turns into fun kinetic energy as we roll down the hill. In other words, you can’t “make energy”. But when you let your team know that you’re all about creating a platform for their flourishing by inviting the best work of their lives, and intentionally creating moments of collaboration that reduce drag, you can start to get the energy in your team moving.

But what are they going to apply their best energy to? What’s the best use of their time and talent? Once you start focusing on the ideal use of your time and talent, and then your team’s, you start to create a powerful feedback loop of energy creation.

The intersection of time and talent: The Zone of Genius

One of my favorite diagrams to draw for my clients is the Zone of Genius map adapted from Gay Hendricks’s book The Big Leap: Conquer Your Hidden Fear and Take Life to the Next Level. The Zone of Genius map plots the best uses of your time on one axis against the best uses of your talent on the other, to create four zones: the zone of incompetence, the zone of competence, the zone of excellence, and the zone of genius.

The zone of incompetence encompasses tasks that are the worst use of your time and talent—others can do these things better than you can. The zone of competence are those tasks that are a good use of your talent but not a good use of your time— because others can do these things just as well as you can. The zone of excellence includes those tasks that maybe aren’t the best use of your talent but they are a good use of your time - these tasks create value and you're good at them. But the highest value you can deliver is in the top-tier quadrant, the Zone of Genius. These tasks are the best and highest use of both your time and your talent, leveraging your unique genius.

Before using the Zone of Genius map as a tool to figure out where leaders should spend their time, it’s important to first ask: What is the job of a CEO or CXO? Some use the metaphors of a firefighter, or a visionary, or a cheerleader. I worked with a CEO who decided to make sure he spent one day a week being a cheerleader, going around the company telling people what they were doing well. The impact was awesome: his team felt seen for their hard work and efforts, and as a result, morale, engagement and retention in the company went up.

Some leadership theorists advocate that, especially for early-stage founders, keeping wide swaths of time open is ideal - so that these leaders can step in to be the firefighter, generating solutions to emergent problems that have no standard procedure or dedicated employee to resolve them. Others suggest that the real job of a CEO is creating the next iteration of the org by getting clear on the biggest vision possible, and communicating it relentlessly.

I say, the CEO should do only those things that fall into their Zone of Genius, —work that doesn’t feel like work, work that gets you in a flow state, work that you can have an outsized impact on, work that creates energy.

For anything that doesn’t fall into this zone, CEOs should hire and delegate to people for whom the tasks do fall into their Zone of Genius (or make a specific plan for doing so when funds are available). Developing a platform for human flourishing means finding talent that loves to solve the challenges that you can’t or don’t get juice from solving. And by “juice” I mean the inner satisfaction that comes from working in your Zone of Genius in order to make a difference on a problem you care about.

I’ve found that when my clients start focusing on their zone of genius they start to notice and appreciate the zone of genius of their team and are able to help their team members redirect their focus towards activities in this zone.

ZOG-obsessed leaders can proactively build a culture of genius—a place where every team member from the CEO on down is expected to understand and operate in their ZOG as much as possible. When people are working in their Zone of Genius, their time is always well spent, and their talent is always well used.

If you want to start uncovering your ZOG, start by doing a time and energy audit. You can find some instructions and guidelines for doing that here. That audit can help you start to zoom in on where your ZOG might be.

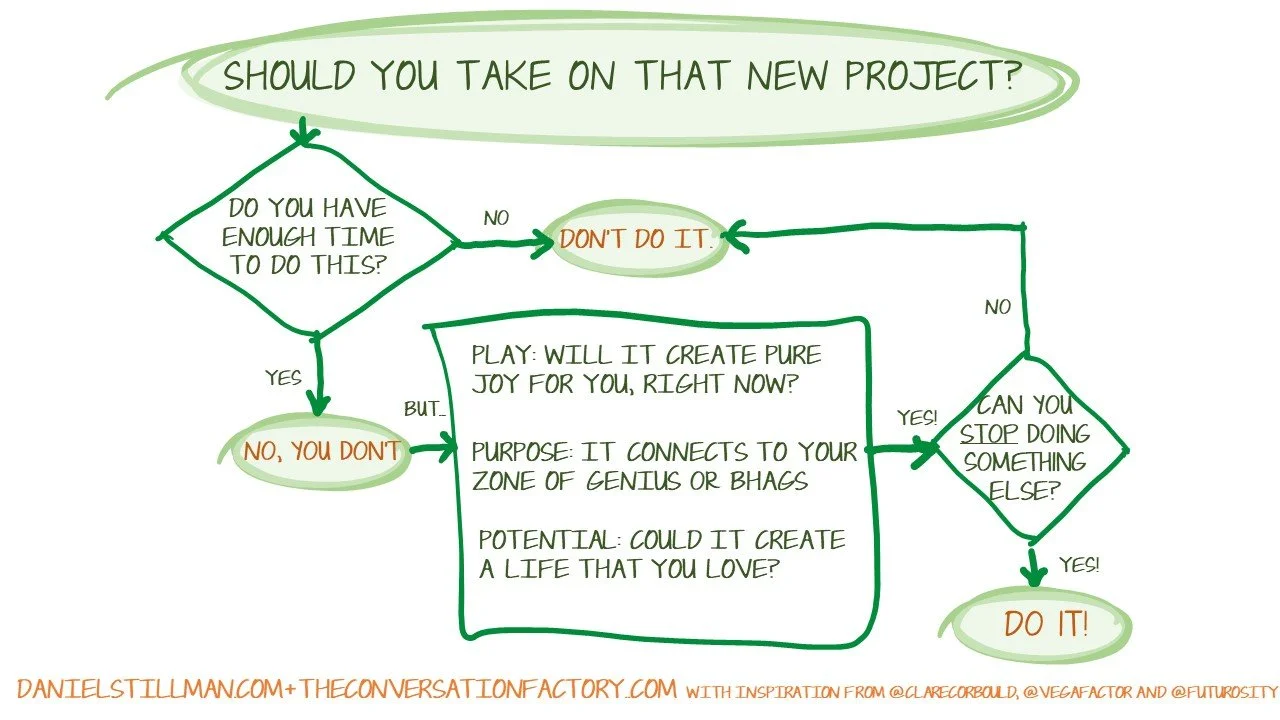

4. Focus on the important and not the urgent

Identifying your ZOG is just the start; actually executing wise time management, learning to delegate, and practicing saying no are an iterative learning process. The truth about time management is that it is, in and of itself, work that we all must learn to do competently. We all have a million things coming at us at once. And our brains are uniquely suited to focus on NOW. It’s a fundamental cognitive bias that has helped us to survive for millions of years. For millennia, if there was food in front of you, you ate it, while you could! Delayed gratification is not a gut instinct for most of us. Learning to focus on what is really important, rather than merely urgent, is why I nearly always introduce my coaching clients to the Eisenhower Matrix, a classic time management framework, because it takes the idea of a “to do” list and makes it much, much more impactful.

Former US President Eisenhower is quoted as saying, “I have two kinds of problems, the urgent and the important. The urgent are not important, and the important are never urgent.” The Eisenhower Matrix plots these binaries (the urgent and the important) on two axes, resulting in four quadrants.

The “Classic” Eisenhower Matrix:

Usually, people rank the priority of the quadrants thusly:

Quadrant 1: DO IT. These tasks are both urgent and important. And you just do them, asap.

Quadrant 2: Schedule it! These tasks are really important but not breathing down your neck. So, put them on your calendar, and do them in a timely manner.

Quadrant 3: Delegate. If the tasks are not important but persistently urgent, or not in your ZOG, get someone else to put it on their DO quadrant going forward.

Quadrant 4: Delete it. As I learned from Randy Paush’s EPIC time management lecture, it’s amazing how much better your life can be if you just patiently and consistently ignore things that are neither urgent nor important. (watch that video. Listening to a person that is rapidly dying of cancer talk about time management is humbling, to say the least. And the fact that the talk is nearly the same as one he delivered using OVERHEARD PROJECTION SLIDES nearly a decade earlier speaks volumes about dying the way you lived.)

Again, because of our millennia-old lizard brains, it’s fundamentally hard to pull away from the DO quadrant, and the tyranny and the urgency of NOW, to focus on the “Schedule It” orange quadrant. These “Not urgent and important” things are exactly those things that will create an outsized impact tomorrow. Focusing further out than today is how you create the most impact. It’s also how you start to tame the tyranny of the urgent and how you inspire your team to get the best from themselves.

It is hard to think clearly, strategically, to focus on our zone of genius, when we are always pulled into the swirl of the DO quadrant. Unfortunately, the way the Eisenhower Matrix is drawn traditionally is deceptive and wrong…each area is not equal, or rather, SHOULD not be equal, in terms of time spent daily, nor is the DO quadrant the one that should be in green signifying “go do it”!

“The urgent are not important, and the important are never urgent”

Remember the quote the Eisenhower matrix is based on. The Important/Urgent quadrant, according to Eisenhower, doesn’t actually EXIST. And it should not be green-quadrant-priority #1…at least not according to the person the idea is attributed to!

I coach my clients and their teams that their IDEAL Eisenhower Matrix should have very, very little seemingly Important/Urgent work and instead focus mostly on non-urgent but important work, because that is how you stay focused on strategy—on creating the future you want, not treading water today. Maybe the ideal Eisenhower matrix actually looks like this: Almost ALL important, non-urgent work (in green, upper right), and some thoughtful delegation work (non-critical and urgent, in blue, lower left). Since the important is never urgent, and it’s a trap, let’s make it a dark, tiny square in the upper left.

Time, talent, and energy unlocked

Maximizing time, energy, and talent is the cornerstone of a flourishing company. Leaders have to start with themselves - by knowing what their Zone of Genius is before coaching their team members to help them do the same.

Unlocking people’s TIME means everyone plays a vital role in driving success by working on the right problem for the organization, but it also means working on the non-urgent problems that help the team stay ahead of the curve - working on tomorrow’s challenges before they become urgent headaches.

Unleashing people’s TALENT happens when leaders hire and delegate effectively, empowering team members to operate in their own Zones of Genius and contribute at their highest potential.

Leaders can unlock the ENERGY of the team through moments of intentional collaboration, facilitative leadership, and the elimination of organizational drag. When the time, talent and energy of your team are aligned in well-facilitated moments of impact, unlocking innovation through sustained creativity is the natural result: a thriving, high-performing organization, where people feel inspired, valued, and supported to do the best work of their lives.