There is more intelligence inside our organizations and our teams than we are using.

It’s the job of leaders to unlock the creative power of their teams - not to generate solutions to all problems for them.

Leaders can do this by leading conversations that leverage the power of a creative process - finding new, unexpected and innovative solutions to challenging problems instead of business as usual.

This creative process has gone by many names, has been studied for decades, and offers leaders powerful, practical tools to drive change and innovation through creative conversations. My book, Good Talk: How to Design Conversations that Matter is just one of many, many books on this topic. In this essay I’ll break down some essential tools of leading creative conversations and share some other books on the topic for your further reading.

At various times, this process has been called Creative Problem Solving (CPS), and more recently known as Design Thinking. Over the decades these approaches have been hailed as practical and functional, or a terribly failed experiment.

While the realities on the ground of how these methods get implemented is nuanced (to say the least!), Creative Problem Solving and Design Thinking work because they leverage some fundamental forces of creative gravity. In my days as a physicist, we liked to joke that gravity isn’t just a good idea, it’s the law.

You try to get a plane in the air without understanding aerodynamics and the fundamentals of gravity! Working with a basic understanding of the laws of creativity means leaders can make meetings soar, instead of feeling like a drag. And yet most leaders are flying blind or working with outmoded theories.

These methods are best learned in action, so…Let’s do an experiment, shall we? After the game, I’ll unpack the five keys to leading more impactful creative problem solving meetings with your team.

I’ve been playing improv games to help teams learn design thinking in action for years. And I remember the first time I saw a colleague lead a group through this particular game more than 10 years ago. At the time, I had taken some improv classes and had already been teaching design thinking for awhile, but had never thought to put them together. It lit a spark in me that still burns to this day. There are many ways to lead this game and to help teams unpack their experience and make meaning of it. This is my approach.

Setting the Scene

I set the scene by asking the group if anyone has done any improv.

Some have, some haven’t.

I remind those that have done improv that we will be “breaking” some of the rules of improv. This will create some discomfort, and I ask for their patience and curiosity with the discomfort.

For those who haven’t done improv, I *also* ask them for their patience and curiosity with the exercise ahead.

Yes, But

“Grab a partner and plan a party together for the next 2 minutes. One person will suggest a party idea. The other will respond with yes, but….

And you’ll continue to offer suggestions, back and forth, always starting with yes, but…”

It’s a simple instruction. If you do this exercise in person, you’ll hear the noise in the room rise as people dutifully try to follow your instructions and have a “Yes, But..” conversation. And one minute later, you’ll hear the chatter in the room die down as people struggle to keep the conversation going.

At two minutes I rescue the room from the pain of continuing.

“What was that like?” I ask

“Painful”

“Hard”

“Slow”

“Argumentative”

…come the replies.

“Did anyone actually get to plan the party?” I probe

Most teams admit that they got bogged down pretty early - where to get the ice became an intractable problem. They got lost in the details.

I draw the axes of Energy over Time and ask the teams - did your energy go up or down during the conversation? The chart below summarizes the overall experience - Energy in the groups drops, fast.

Now, there will be one or two pairs who had a BLAST during this conversation. In some organizations the proportions of “Yes, but” enjoyers are even higher.

“I loved how they kept poking holes in my ideas and I had to find solutions!”

But the room as a whole admits that such conversations create a one-sided effort that does wear thin over time since poking holes is a lot easier than plugging them.

The main points I want teams to notice is that:

Many people do not enjoy “Yes, But” Conversations.

Some people like “Yes, But” Conversations

Overall, “Yes, But” conversations drain energy

Yes, And

“Grab the same partner. The other partner now gets to suggest a party idea. You’ll continue to offer responses, back and forth, always starting with yes, and…for the next 2 minutes”

Again, if you do this exercise in person, you’ll hear the noise in the room rise as people dutifully try to follow your instructions and have a “Yes, And..” conversation. And one minute later, you’ll hear the chatter in the room continue to rise as people really get into the party ideas

At two minutes I have to shout to be heard and get the room to settle down.

“What was that like?” I ask

“Fun”

“Energizing”

“Collaborative”

“Flow”

…come the replies.

“Did anyone actually get to plan the party?” I probe

The room usually explodes with people ready to launch their party ideas into the stratosphere.

Returning to the Energy X Time Chart, I ask the room how the arc of their energy was for this conversation.

“Was it going up and to the right?”

Most of the room agrees.

“Or was it starting to level off?” I enquire

Now, in a mirror to the “yes, But” portion, there were several pairs who felt like the “Yes, And” energy was getting to be a bit much towards the end of the conversation. Could they really afford Jay-Z and Beyonce for this intergalactic unicorn party on the moon? Who was going to fund the rocket flight - Bezos or Musk?! Things were starting to feel a bit out of hand for some.

At this point, I want the group to understand:

“Yes, And” Conversations are energy producing

Some people run out of steam with “Yes, And” Conversations

Different people run out of creative energy at different rates.

It is the job of a leader to make space for these modes of creative thinking. We need “Yes, And” thinking to make sure we have MORE creative ideas on the table. And we need “Yes, But” thinking to make sure the ideas actually hold water.

Opening and Closing at the same time sucks

At this point, I can point out the fundamental problem:

There are people who LOVE poking holes in ideas.

There are even folks who love having their ideas being poked.

But generally speaking, it’s more energizing to build on ideas.

So why are our creative meetings so broken?

The problem is that teams are generally playing BOTH games at the same time. We have all been in meetings where people are simultaneously generating and destroying ideas.

“What if we try___________?”

We did that last year… it didn’t work.”

“What if we try___________?”

“We can’t get that past legal.”

“What if we try___________?”

“That sounds expensive”

Like a quantum foam of particles being born of the vacuum and disappearing from existence in an instant, almost nothing escapes this kind of meeting, where “Yes, And” people are cut off by “Yes, But” people before ideas even get to develop or mature.

The leader who understands the physics of creative conversations makes sure we play both the “Yes, And” and the “Yes, But” games ONE AT A TIME.

Yes, And is Opening. Divergent or Generative Energy.

Yes, But is Closing, Convergent or Subtractive Energy.

Electrons and protons are negatively and positively charged, respectively…but we need both in balance to make up the universe we live in.

So, too, do leaders need to balance positive and negative energy to drive creative thinking.

Creative Culture is limited by classic Cognitive Biases

At least two common cognitive pathways keep us from pushing through “Yes, But” thinking into new and innovative solutions: The Loss-Aversion Bias and the Negativity Bias.

The Negativity bias is thought to be an adaptive evolutionary function (Cacioppo & Berntson, 1999; Vaish et al., 2008; Norman et al., 2011). Our prehistoric ancestors were exposed to environmental threats that were truly threatening - the sound of snapping branches in the woods could actually be a tiger or worse. Being highly attentive to potentially negative stimuli played a useful role in survival. Seeing gaps and challenges in ideas as fatal flaws to be avoided at all costs makes us flee from new ideas.

The Loss-Aversion Bias is summed up by the old saying “A bird in the hand is worth two in the bush”. Loss aversion was first proposed back in 1979 by Amos Tversky and Daniel Kahneman as an important framework for prospect theory – an analysis of decision under risk. We feel the possible loss of, say $10, much much more sharply than the gain of $10. Investopedia suggests that “human beings experience losses asymmetrically more severely than equivalent gains. This overwhelming fear of loss can cause investors to behave irrationally and make bad decisions, such as holding onto a stock for too long or too little time.”

Samuelson and Zeckhauser, in their 1988 paper “Status quo in decision making” pointed out that incumbents do much better than they would in a neutral election.

These cognitive biases keep us rooted in protecting what we have instead of exploring new possibilities - because doing so costs time and energy.

Creative leaders make space for Opening, Exploring and Closing.

In 2010 I read Gamestorming: A Playbook for Innovators, Rulebreakers, and Changemakers. Gamestorming brought together decades of practical wisdom and research into how groups can work together, better by thinking of work through the lens of game theory.

Yes, And is a Game. The rules create an additive thinking space.

Yes, But is a Game. The rules create a thinking space of subtraction.

It’s easy to get frustrated when you are playing a different game than everyone else on the field. Can you imagine trying to play soccer while everyone else is playing rugby? Or playing chess while your partner is playing backgammon?

It’s impossible to make any progress this way.

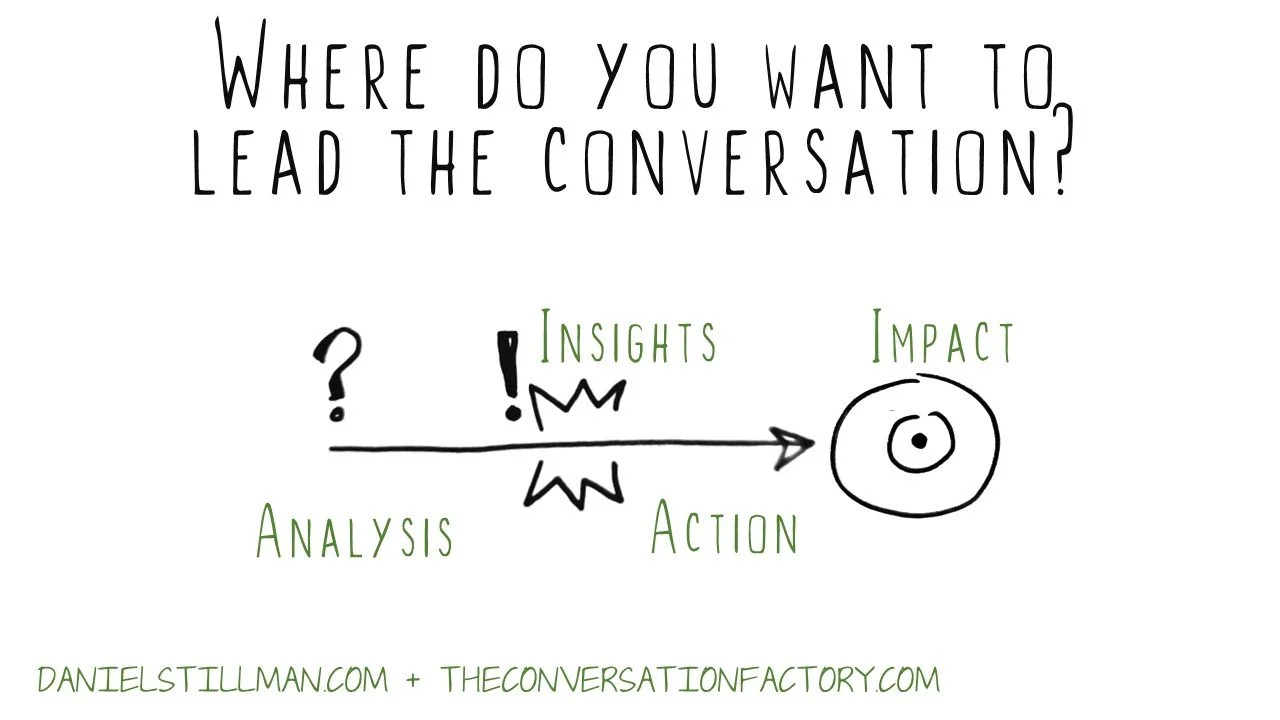

Gamestorming opened my eyes to the importance of balancing these three games, in sequence, as in the diagram of a creative process below. The authors also opened my eyes to a third energy: Emergence, or exploring.

Opening: Divergent (positive)

Exploring: Emergent (neutral)

Closing: Convergent (negative)

In the universe, we have electrons and protons, but it’s actually neutrons that help hold atoms together. And just so, a culture of innovation is found in making space for creative emergence - a kind of “neutral” space, where we are not generating or eliminating ideas, but holding space for them to be heard and to combine and recombine.

Openers love opening and may resist closing.

Closers love closing and may drag their heels in opening.

Almost everyone finds exploring a bit challenging, which is why Sam Kaner’s Facilitator's Guide to Participatory Decision-Making describes this middle part of the creative process as the “Groan Zone”.

We all need to become switch hitters in the creative process if we’re going to work together.

Openers need to learn to close - to choose and launch

Closers need to learn to lean into opening, to get curious about ideas before poking holes in them.

Leaders can create the guardrails for conversations that make this possible.

Creative Leaders are Multipliers

Leaders have an outsized influence on how teams solve problems. They can intentionally set up a space where these three modes of creative conversation can flow. If they know where the rough air is going to be in the process, they can plan for it.

For example, in her bestselling book Multipliers: How the best leaders make everyone smarter, Liz Wiseman posits that there are at least two types of leaders

- Multipliers, who expect great results from their teams AND create the conditions for genius to emerge

and …

- Diminishers, who micromanage, take credit and waste the genius in their teams and organizations.

Multiplier leaders provide the support and forward movement for teams to navigate the perilous middle of the creative process with grace. They expect great results and know that setting time aside for thinking through options and opportunities creates the best results - what Daniel Kahneman calls “Thinking Slow” in his book “Thinking: Fast and Slow”.

How might we create the conditions for effective creative thinking for our teams?

At this point, the hour is coming to a close and there’s precious little time for much more than reflection and projection - getting people who’ve gone through this improv game to think about what it was like, and how they might lead differently in the future. And for them to share what they might already be doing that looks and feels like what we’ve been talking about for the last 45 minutes or so.

Five Steps for Leading Creative Conversations

Make space for Opening, Exploring and Closing. Doing all three in one short meeting may not be possible or feasible at first.

Open with a clear challenge statement. What problem are we here to solve? Defining the problem well is a powerful form of creative leadership. More on that here.

Open Pt 1: Think alone, then think together. Get everyone to write down their ideas in silence. For more on why, check out “Your next meeting should be silent”

Open Pt 2: Get people to share their ideas. No “Yes, But” energy allowed…yet!

Explore: Share ideas and remix them. Combine the best parts of ideas together. While some people criticize collective creativity with the saying “A camel is a horse designed by committee” I challenge you to cross the Sahara desert on a horse!

Close: Decide on one or more ideas to prototype, test or evolve.

Step Zero should usually be “Decide how you’re going to decide”.

Leaders need to set groups up for success by letting them know if this is a democracy or an advisory committee. Leaving things vague just causes a mess.

Step Six should usually be “Let’s talk to real people facing the challenge we described in step one without showing them our ideas yet” so that we reduce the chances of a third dangerous and common cognitive bias - the Confirmation Bias, ie “the tendency to search for, interpret, favor, and recall information in a way that confirms or supports one's prior beliefs or values”.

In the Toyota System of continuous Improvement, this is called Genba, or Genba Walks - “going to the real place where the actual work is done”

Leadership is Designing and Facilitating the conditions for Transformative conversations.

Left to our own devices, conversations will be an unstructured mix of “Yes, And” and “Yes, But” modes of working. Leaders have the opportunity to set up conversations to run on a different operating system - one where teams cycle through “yes, and” and “yes, but” thinking in ways that create respect, psychological safety and forward movement.

This mode of leadership isn’t directive or authoritative, but is more akin to the style of leadership Daniel Goleman described in HBR in 2000 as a Leadership That Gets Results - a coaching mode of leadership. Coaching and Facilitation are two sides of one coin - leadership based in empathy and an understanding of how humans are built - but that’s a conversation for another time.