Your Team Meetings Might be Leaky

Do your meetings always start and end on time?

Does everyone join at the exact call time, or do people trickle in?

Do people sometimes need to “hop off early”?

Does all the work on the agenda happen in the meeting, or does the work spill over?

If any of the above feel true, your gatherings might be leaky.

Leakiness can become even more pronounced over the course of a multi-week or multi-month project - Leakiness can look like when a team needs to make an important decision and an important decision maker isn’t there.

Leakiness makes it hard to get things done.

It can be hard, maybe even impossible, to have a proper conversation, to come to a realistic or powerful decision or conclusion when the same people aren't in the conversation from the beginning to the end.

Throwing Vegetables at the Stove

When you cook, do you gather your ingredients, toss them at your stove, turn up the burner and then walk away… and hope that dinner will be ready in 30 minutes?

No, of course not! Process matters.

You need to prep your veggies. You need to add the ingredients in a certain order, depending on the results you want.

And you need to pick the right container and the right temperature for your dish.

And for nearly every recipe, you need to raise and lower the heat at different moments in the process.

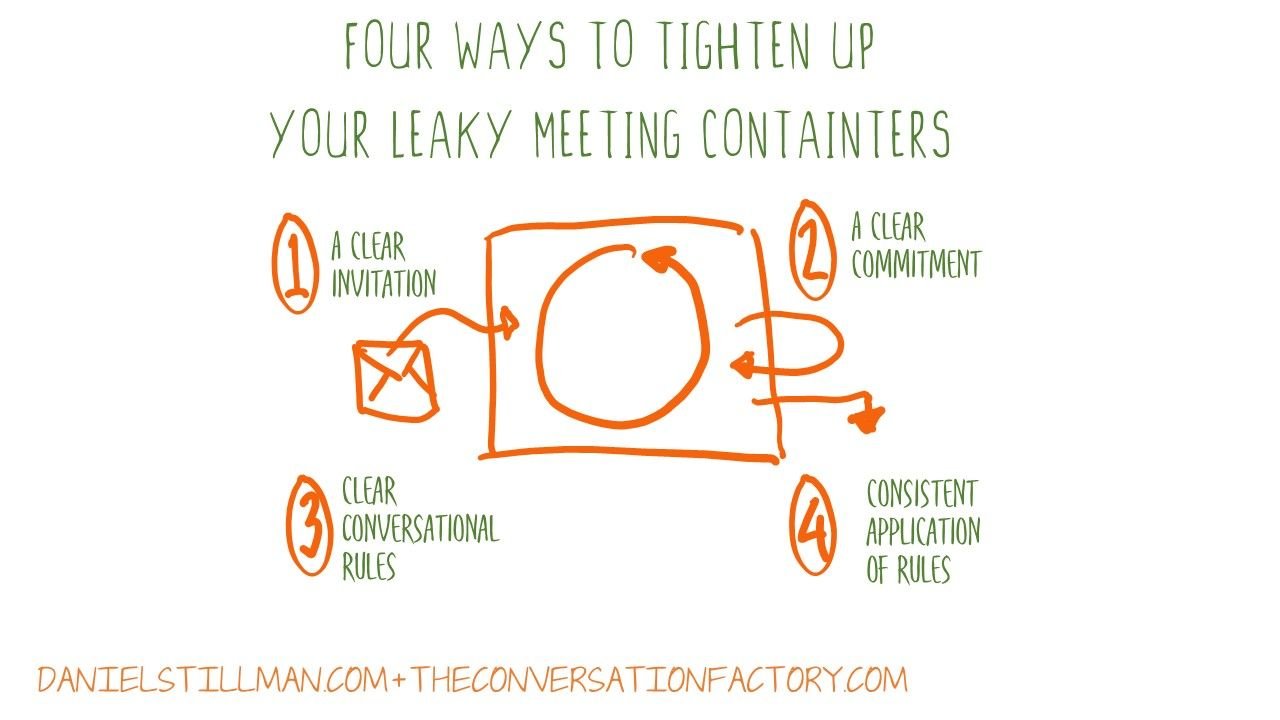

Four ways to Tighten up a Leaky Meeting Container

When you have a “leaky” container, things don’t heat up or get “well done” the way you might want them to. If you leave the door to the oven open, your turkey will never really cook. Similarly, if your board meetings are poorly run, or your leadership team gatherings or offsites are haphazard, your company simply will not be able to “cook”, i.e. get things properly done, either.

There are four simple ways to tighten up your container, and I think about them visually, like this:

How do we enter? How do we know we can leave or that we need to stay? How do we act when we’re in the container? And most importantly, how do we know we’re “out of bounds”?

In other words, you need:

Clear Invitations

Clear Commitments

Clear Conversational Rules

Consistent Application of Boundaries

1. Clear Invitations

When I was writing my book, Good Talk, about how to design conversations that matter, I was tempted to title it “What the F*CK are we talking about?” since I felt like everyone has, at some point, wanted to ask this very question.

What is this meeting really about? And are we really talking about the right things?

A clear invitation means the goal, the purpose and outcome of the conversation/meeting/project is clear - clear enough for a person to be able to commit to the conversation.

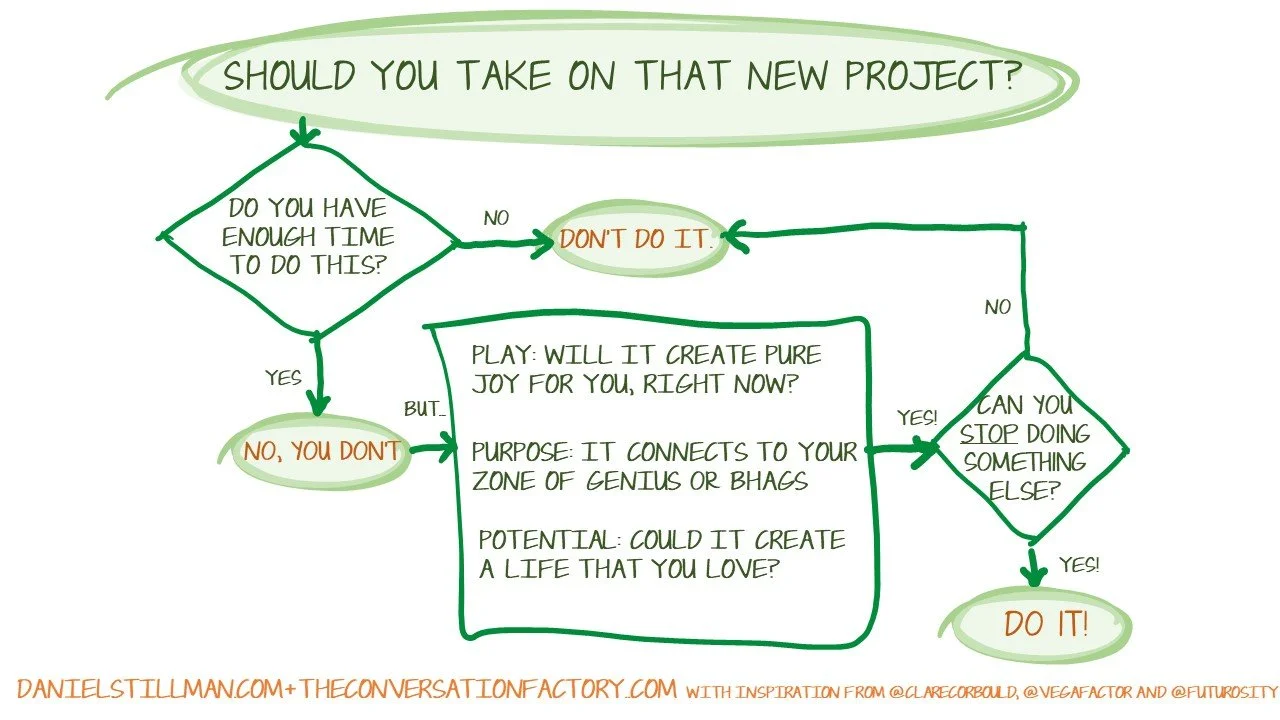

Powerful invitations tap into powerful sources of motivation. Psychologists generally agree that there are two primary types of motivation: internal (or intrinsic) motivation, and external (or extrinsic) motivation.

The top Intrinsic motivators, in order of potency, are play, purpose and potential. These three could also be thought of as direct motivations.

Play is the most direct and durable: Come and play...it’ll be fun! Purpose is next, focusing on near-term impact; while potential is about long-term impact.

The most powerful conversations and tightest containers tap into intrinsic sources of motivation. The more you can connect your invitations to the purpose and potential of each person involved, the better.

If you want to know more about the art of invitation, I wrote a whole chapter about it in my book Good Talk.

The simple way to practice this is by giving your meetings a descriptive name. Don’t call it a budget meeting. Call it “Collectively decide what we’re going to spend money on for 2023”. Or “discuss options for budget spend” if you’re going to make the final call.

2. Clear Commitments

Are you in or out? Are you coming or not?!

One of the reasons that a workshop can be such a powerful container for getting work done is that clear amounts of time are blocked out for the work, ideally with all of the right people in the room, for the whole time of the gathering.

In a design sprint, a team commits to five days of focused work. On day five, a team commits to testing an idea with customers, regardless of whether the concept feels fully baked or if the team is really ready or not.

The commitment from the whole team is to come for five days, and to clear their calendar. If someone wants to leave on day three, it’s possible that you can push back, and remind them of their commitment to be fully present for the whole five days.

A commitment has a start and an end. That commitment could last a week, a month or a year. It can be specific, like agreeing to show up on Wednesdays at 1pm for an hour, every other week for 12 weeks. Commitments can be more general, like “looking over a document.” The more specific a commitment is, the easier it will be to agree to and the easier it will be to reinforce (#4!).

A challenge I’ve had with clear commitments is in longer-term transformation and leadership development programs. Over weeks and months, people get pulled in many directions, and lose focus…the steam escapes from the container and the pressure drops. Usually, only a small fraction of the people who responded to the challenge and the invitation are still deeply committed at the halfway point.

So, either ask for shorter commitments…or recruit a smaller group of people. Fewer people means less diffusion of the commitment across the group, sometimes called “social loafing”.

This is why I often share my research on Minimum Viable Transformations with folks leading transformational projects. A big change only needs about 3.5% of a group to be consistently and actively engaged. So…get clear on who that 3.5% is as soon as possible and engage with them to maintain consistent commitment!

Clear commitments aren’t just about showing up. Clear commitments can also mean staying engaged *during* a gathering and also *between* gatherings.

Do you have a system to track and follow up on action items? And do you have to chase people to have them do what they said they would? That’s some leakiness, right there.

This also means that you are not getting the full value out of the meeting.

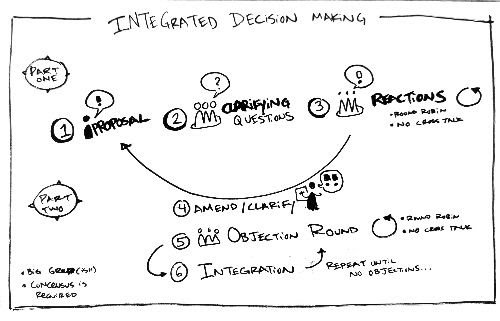

3. Clear Conversational Rules

This is a rather broad category, but I’ll give you some examples.

In the documentary Stutz (which is amazing!) Jonah Hill films himself unpacking critical thinking tools with his therapist, Stutz. Hill suggested that we sometimes want our therapist to give us advice and we want our friends to just listen to us. But instead, it’s the other way around…our therapist just listens, and our friends “who are idiots” give us advice.

Conversational Rules can simply look like clear boundaries.

Show of hands if anybody has ever gotten advice when they just wanted to be listened to? Or gotten advice, but the wrong kind!?

Sharing work for critique with a larger team is a great example of this. Being clear on the challenge you’re solving, what your blockers are and what you do and don’t want help or feedback on is part of the job. Check out my podcast episode on designing a culture of critique here for some insights on designing this crucial conversation.

Setting up clear boundaries is an act of Conversational Leadership.

In my coaching mastermind group when we share a challenge we make it really really clear:

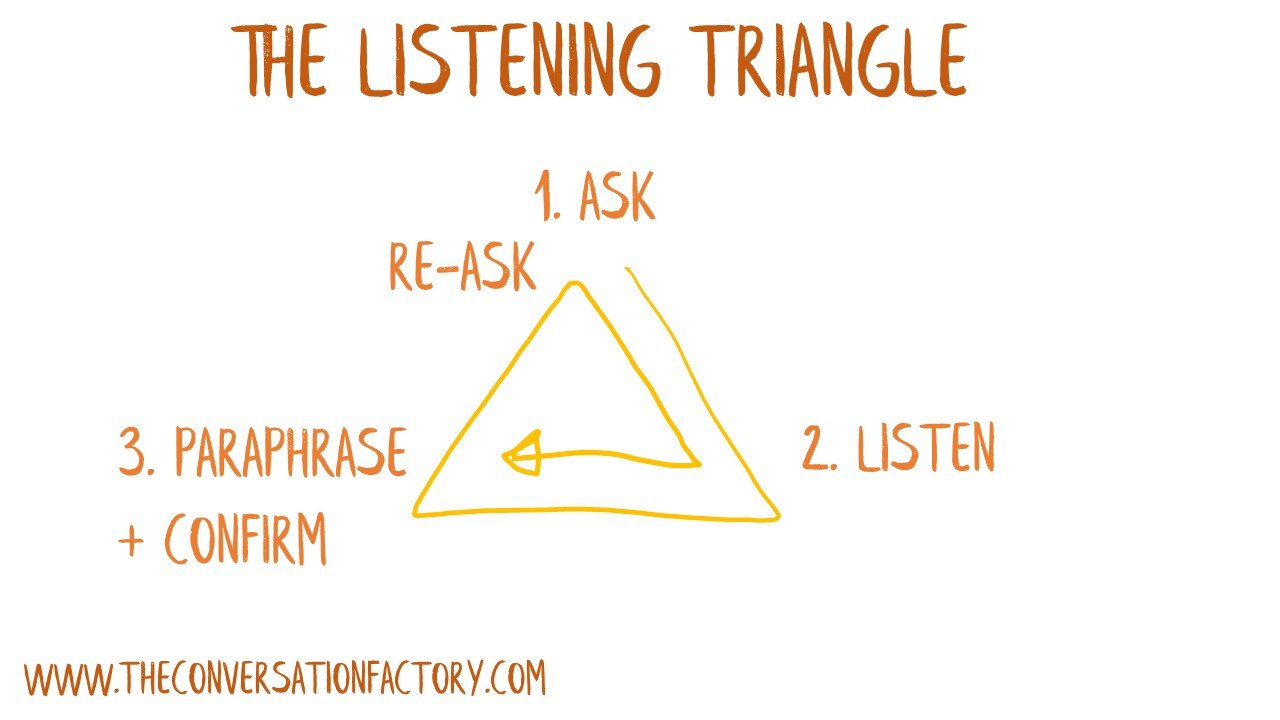

Do we want coaching on this challenge?

Do we want advice?

Do we want people to share their own experiences with similar challenges?

Similarly, I regularly pause to set up conversational rules with my wife. If she shares a challenge from work or her life, I ask if she wants empathy, coaching or brainstorming, or something else.

I learned this approach largely from my men’s group facilitation training. In my men's group we're very clear on boundaries. We only ask questions that help someone go deeper into their own experience of their challenge. We focus on emotions and sensations over stories and enforce that boundary.

We never offer advice.

Clarifying the rules and boundaries of any conversation is key.

You can do this with the group or offer guidelines and suggestions to lead the way.

The clearer the invitation, commitments and rules, the tighter (ie, less leaky) the container for the conversation is.

4. Consistent Application of Boundaries

If you set up a container and never push back or reinforce the boundary when someone breaks a commitment or violates a rule, you wind up with a leaky container. And leaky containers are draining. People see that the boundaries of the container are porous, and things go downhill from there.

If someone misses a meeting and you say nothing, the rest of the group notices this.

“Do the commitments matter, or do they not?” the team wonders…

If the conversational rule is that each person speaks once in a round, with no cross-talk or advice, and someone breaks that rule, do you let it slide without saying anything? Or do you remind the group of the rules and ask them to continue?

One important rule - consistent application of boundaries isn’t policing. Generally speaking, people don’t like feeling policed, forced or coerced into following rules. Make sure people understand why the rules, boundaries and commitments exist, and reconnect them to the invitation or purpose of the gathering in the first place.

In Harvard’s Negotiation Institute they suggest being “hard on the problem and soft on the people”...so, we’re never faulting a person, or making them wrong…we’re asking everyone to re-engage with the boundaries for the good of the whole group.

Tight Containers Help You Get Things Done

According to Cook’s Illustrated, a cover helps water boil faster, but not by much…a covered pot boils in just over 12 minutes and an uncovered pot boils in 13 minutes and 15 seconds.

But when you lock that lid tight…that’s when you really cook!

Growing up, I knew that my mother loved her pressure cooker and used it for almost everything. Why? Because a pressure cooker has a tight lid.

With that tight lid, the water temperature rises higher and the ingredients cook faster. That’s why instapots were the “it” gift a few years back…they’re not quite instant, but they're faster than your stockpot.

(As with so many other things, the world eventually realized my mom was onto something good!)

In a pressure cooker, instead of boiling at the usual 100 degrees Centigrade, water boils at 121 degrees. That 21-degree increase means a stew that would normally boil for an hour COULD be done in 20 minutes. That’s HUGE.

Locking your container tight gives you a cooking time that's two-thirds shorter.

Getting Things Done Increases Engagement

Disengagement is the biggest issue facing leaders of teams today. Depending on what stats you look at, easily half of employees are disengaged in the workplace. We come to work to offer value, to achieve our goals, and to make progress. Our leaders are there to help make that possible, to remove the barriers to progress. Getting things done, seeing the results of your work, is satisfying, addictive even.

When we feel no progress is being made, it’s an energy suck. When someone walks away from a meeting you’re hosting with a sense of frustration, eventually this becomes burnout, disengagement and churn.

When I run 360s for leaders, one of the key questions I ask their direct reports is “are you able to create extraordinary results with this leader?”

If you’re unsure of how your team would answer, it’s time to start tightening up your leaky containers.

The most powerful way to tighten up any container is to come into the present moment and feel the energy in the room, whether it’s virtual or physical. Does the group feel coherent, clear and energized? If not, slow down, and have the conversation about Invitations, Commitments and Conversational rules. It can take a few moments to tighten up the lid on the container, but it’s always worth the effort to really get things cooking.