Let’s talk about meetings

A few years ago I read an article about the key types of meetings any team or organization should be having…but the ONE type of meeting they said you should NEVER have is a meeting about meetings!

A chill of cold fury (or was it sadness?) ran through my body.

A meeting about meetings is without a doubt, the most important meeting to host with your team.

Right now. Or…as soon as you read this essay!

Virtual meetings are here to stay AND we’re all burnt out to a crisp.

So, let’s delete some meetings on our calendars if we can. But how? There’s so much to get done!

Meeting about meetings #1: Where are we on the trust and communication curve?

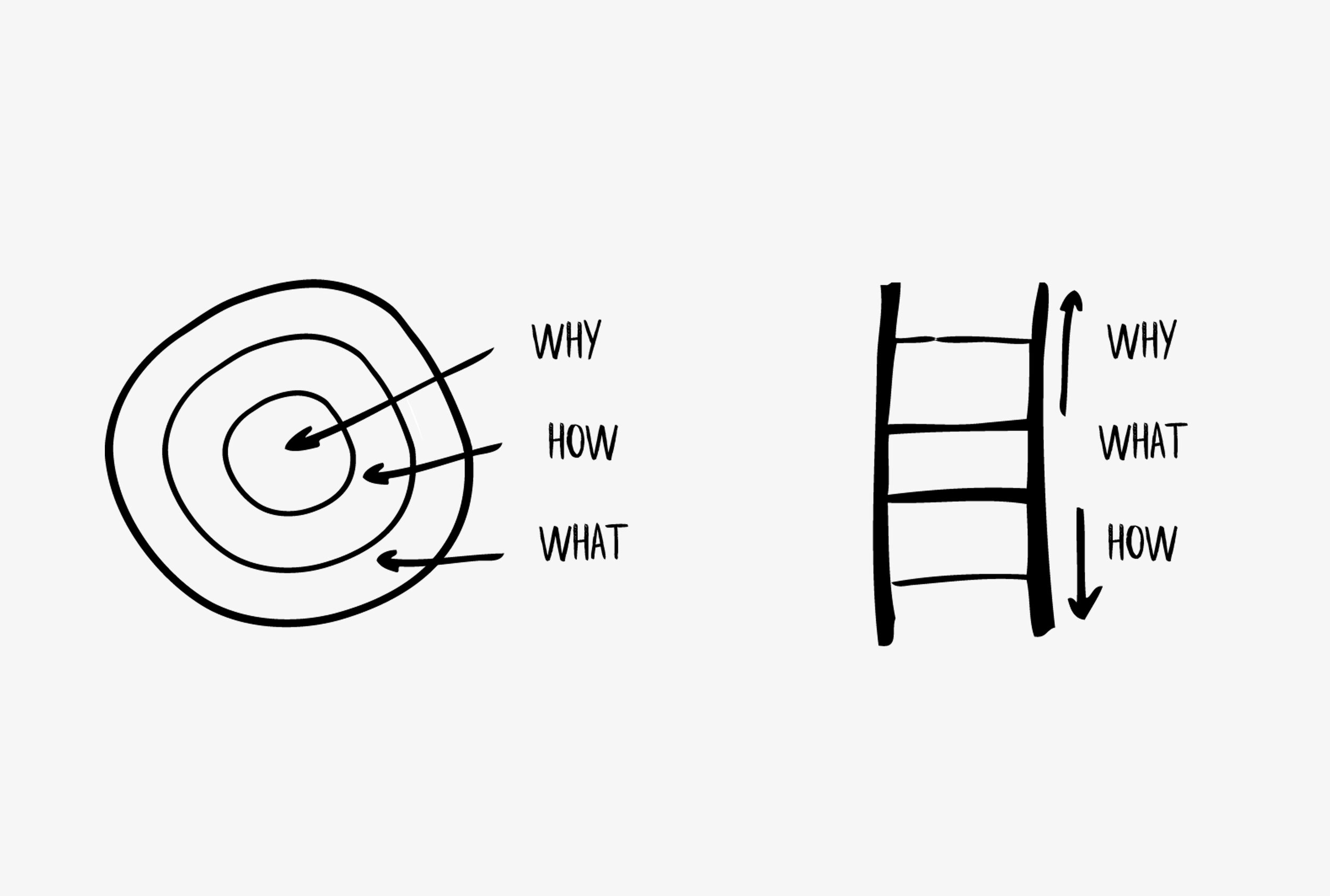

My podcast conversation with Emily Levada, who was then the Head of Product at Wayfair at the time of our conversation, but is now the Chief Product officer at Embark Veterinary, advocates for a team conversation based on a simple diagram, pictured below.

Ask your team to silently note and anonymously map together answers to:

How much trust do I think this team has?

Are we spending too much time talking or not enough?

As Emily points out, when there’s total trust, there’s also a sense of safety - When my collaborators trust me to make things work, I feel empowered to find my own way, without calling for a meeting.

If trust is low, add strategic communication to deepen it - not just more meetings, but meetings with the aim to increase transparency and connection. Work with a team coach and focus on creating the conditions for increased trust.

If trust AND collaboration time is high…find ways to remove collaboration time. One way to do it is by learning to work together asynchronously, which I’ll talk more about in Meetings about Meetings #3.

Meeting about meetings #2: How do we talk when we talk?

Groups can move mountains if everyone is pushing in the same direction. More often, group conversations ping pong back and forth. The conversation flow gets stuck, drifts, or overheats.

Someone usually speaks first when the team lead shares a challenge or issue. The conversation can get anchored to that first turn.

I call it “first speaker syndrome” and one way to solve it is to not talk at all in your meetings!

Try a silent meeting, video off, with everyone in a document together.

Silent, video off meetings can be incredibly relaxing. Like Study Hall was back in High School.

Or, just tame the complexity of the group conversation with better turn taking rituals.

It’s hard to listen to two people speak at the same time. In fact, it’s nearly impossible. Listening to one person talking takes about 60 bit/sec of attention…and our entire attention span is 120 bits/sec!

Try a round robin, or ask people to “pass the mic” so that each person speaks on a topic to open the floor up. Being clear about who’s going to talk and for how much time isn’t being bossy…it’s helping everyone with clarity and leadership so that the conversation can be inclusive and fluid. For extra credit, if you want to really stretch your turn taking patterns, I’m a fan of Quaker style meetings which set a high bar for taking a turn:

Everyone waits in shared silence until someone is moved by the Spirit (i.e. has a strong religious feeling) to share something

A person will only speak if they are convinced that they have something that must be shared, and it is rare for a person to speak more than once.

The words should come from the soul - from the inner light - rather than the mind.

Meeting about meetings #3: Do our rituals and patterns serve us?

My friend Glenn Fajardo co-authored a book called Rituals for Virtual Teams. I was so excited to host him on my podcast and have him share his copious wisdom about helping teams collaborate better from afar.

One thing Glenn excels at is cross-time-zone, asynchronous collaboration. A lot of folks feel like synchronous video and audio (ie, Zoom calls!) are the best (and only) way to connect remotely...but Glenn suggested that video messages can be amazingly connecting, and even more powerful because they are asynchronous. Tools like Loom, Dropbox Capture or even WhatsApp can make remote, asynchronous collaboration fun and efficient.

Design the Moments of Meeting with Occasion, Intention, and Action

Glenn suggests (and I do too!) that you do an inventory of the meetings and moments of interaction for your team. (What are the Occasions?)

Find ways to declare, clarify and if needed shift the Intention so the moment really serves the need the team has.

Action has two lenses: One is what action do you want people to do or take at the end of the occasion/intention moment? Being clear on this can help you lead thoughtfully designed actions...and the more often you host these, the more they will become rituals, ie, core artifacts of your team’s culture, that anyone can start leading.

In short: create an inventory of your team’s essential moments and find a pathway to make those moments create the team experiences you intend to create. It is, as Glenn says, as simple as asking:

“How do we want people to feel in those different moments in a team's lifespan? And then, what are the actions that we could associate with those things?”