The secret of transformative facilitators

When I coach facilitators, one thing I notice is how overwhelming the job can feel. There’s a lot to keep track of: Stakeholder requirements ahead of a session, bringing together people for a working session (cat herding!), keeping your eyes on the goals and outcomes to make sure that the time was well spent…all while making sure that all voices are heard and included…*and* while keeping an eye on the agenda, flexing and shaving time where needed.

It’s a lot.

If there’s one thing I want facilitators, leaders and coaches of all stripes to remember it is this: Never do anything for others that they can do for themselves.**

The less you do, the more they own.

Collaboration is Group Learning

More and more, I’m aware of this simple fact: True collaboration is a group learning process. The group needs to learn:

What everyone else thinks about the challenge: What is happening? What’s the real challenge?

What they themselves believe is possible — what futures can be created with this group?

What does the group believe is possible?

What are we willing to try? How much risk are we willing to endure?

How committed is the group to the challenge? Who and how will things be seen through?

If we know the answers to these questions, there’s no need for a collaborative session!

Never touch their paper

Last week I was working with a group on deepening their abilities as teachers and coaches — the group was at the start of a journey from being masters of sprint facilitation to becoming teachers and coaches of others. During this 2-day session I shared a story about the teacher who has taught me the most — my origami mentor, Michael Shall, who I apprenticed to in my teens. This story showed up in a surprising number of post-session reflections, so I feel it’s worth resharing.

I learned a lot from Michael: About the importance of clarity in instruction, about the value of harnessing your largest voice to capture the attention of a room…but most importantly, he reminded me to never touch their paper.

While he would teach an origami model, step by step from the front of the room to a group of 100 middle schoolers, I would wander the room and check in on people. Was anyone struggling?

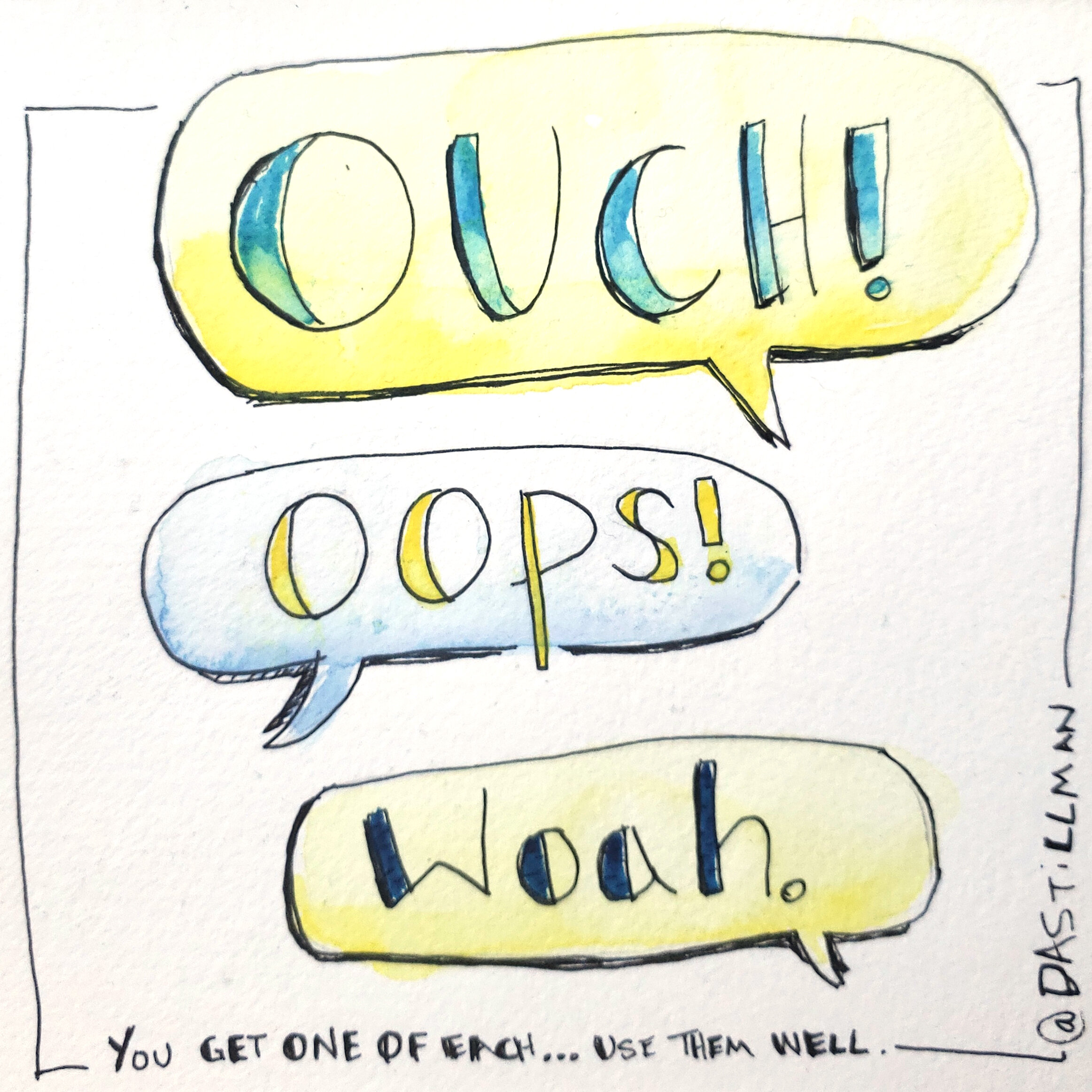

It was not my job to fix their challenges by finishing the move for them. It was my job to help them keep trying.

Michael caught me “helping” a student once by finishing the step for them. He took the paper from my hands, undid the step I made for the student, and handed the paper back to them, and gave them a clear and crisp direction on how to finish the step, which they then did. He pulled me aside and taught me that lesson that I keep with me to this day: never touch their paper.

By touching the paper of the student I was taking away their temporary frustration, but robbing them of the chance to figure it out for themselves.

Why is this so important?

The Kolb Cycle of Learning

In the early 1970s, David A. Kolb and Ronald E. Fry developed their experiential learning model (ELM), which suggested that there were four key elements in learning:

Concrete experience

Observation of and reflection on that experience

Formation of abstract concepts based upon the reflection

Testing the new concepts

My taking the paper from a student robbed them of the concrete experience of working the step out for themselves, taking away their first step in the learning process.

Similarly, if a facilitator steps in and makes a process too easy for a group, by synthesizing ahead of where the group is, by giving them a word rather than letting them find their own…that facilitator is “taking the paper” from the hands of the group. From that moment on, the work the group is doing may not be fully owned by that group.

Lazy Facilitation

Stepping back and letting the group figure things out for themselves means the facilitator can exert effort and attention at the most critical points, in the most thoughtful ways…in order to make sure that the group really does the work and really owns the outcomes.

Lazy facilitation also means setting up structures and systems that allows the group to manage itself…it’s not unleashing chaos on them!

A few structures and systems Micheal used:

Cheating vs. Sharing

Michael always used to tell a group:

“In school, if you copy from your neighbor’s paper it’s called cheating. In origami it’s called sharing”

This radical transparency allowed a group to teach itself. If someone was struggling, they could feel free to glance left and right and see if some help was at the ready.

In large workshops, I ask groups to do the same — they can look over at the other groups’ work (whether it’s on a wall or on a Mural online) and see what’s supposed to be happening.

Show me what I’m showing you

Another phrase Michael taught me was “show me what I’m showing you”. He always folded the model the group was working on in much larger paper…after a move was finished, he would hold up his giant model and ask everyone to do the same. In one quick moment, the group could check in on where they were supposed to be, what “good looked like” and at the same time, he could scan the room and see, at a glance, where any big issues were…and send me over to help them out.

In group work, I use this principle often — having a finished template or simple diagram to refer a group to can get them towards the right direction, without doing it for them.

Breaking things down

In this way, facilitation is helping a group by breaking complex moves into clear, crisp steps. This is where Michael’s genius was. He built thoughtful vocabulary for groups — helping them learn the difference between a “raw” and a “folded” edge, to notice the angle a paper was being folded to, seeing the shapes we were making with our hands. He helped us see the paper’s structure and gave us clear guidance, step by step.

Facilitation means “making things easy” but not by doing things for people…we make things easy by asking the right questions and breaking the challenge down into clear steps.

Origami for Teams

If you want to learn more from Michael, I wrote a short book with four origami-based exercises I learned through him. It’s called The 30 Second Elephant and the Paper Airplane Experiment. It’s a fun and strange little tome, just like Michael was.

** it turns out that Michael’s wisdom is reflected in other places. He’s not the only advocate of self-management! This quote, “Never do anything for others that they can do for themselves.” is sometimes termed “The Iron Rule of community organizing” and is attributed to American community activist and political theorist Saul Alinsky.