"If we have our own why in life, we shall get along with almost any how."

Friedrich Nietzsche, Twilight of the Idols, or How to Philosophize with a Hammer

Where do we want to go, together?

I first encountered the Nietzsche quote on the above in Viktor Frankl’s excellent book, Man’s Search for Meaning. Frankl survived the horrors of the Holocaust in World War II and found in this experience an opportunity to practice his philosophy of logotherapy. In essence, his approach suggests that our task in life is to find and live our purpose—our why—and to imbue the how of life with that purpose.

Simon Sinek’s TEDx talk, “Start with Why,” has been viewed 64 million times (at the time of this writing). Like Frankl, Sinek says that we must start with the why. Once the why has been locked in, the how and what come much more easily.

While Frankl and Sinek are not wrong to bring our focus to why, I would offer that why is not more critical than how. Why and how exist in conversation with each other. A why without a how creates big-picture ideas that are just castles in the air. A how without a why has no soul.

At least in a business context, it’s not always helpful to insist that why is more important than how. Strategists (why-people) are not more important than engineers (how-people). Conversations can get caught between big-picture people who care more about the why, and laser-focused people who care more about the how. You need both to get the job done.

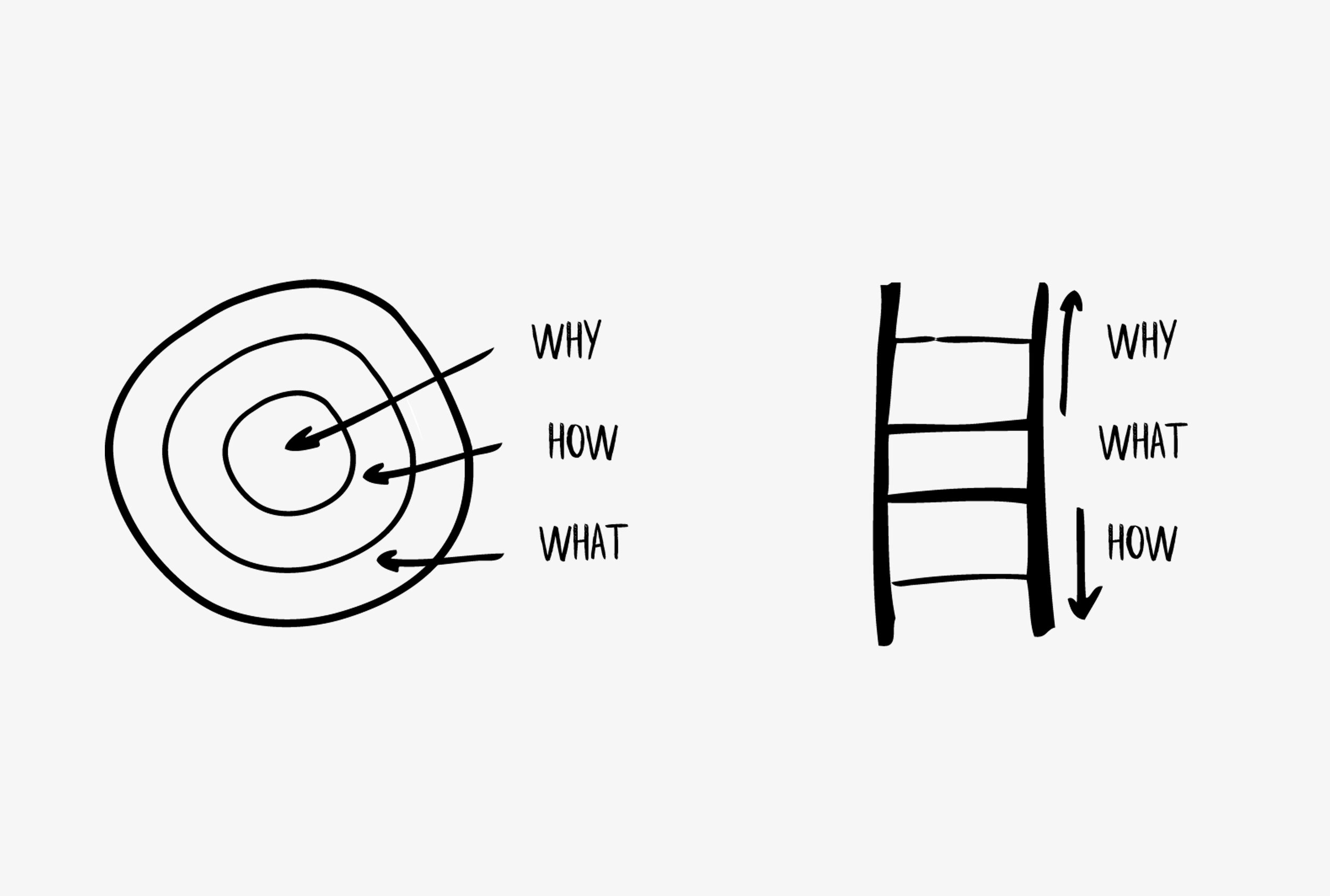

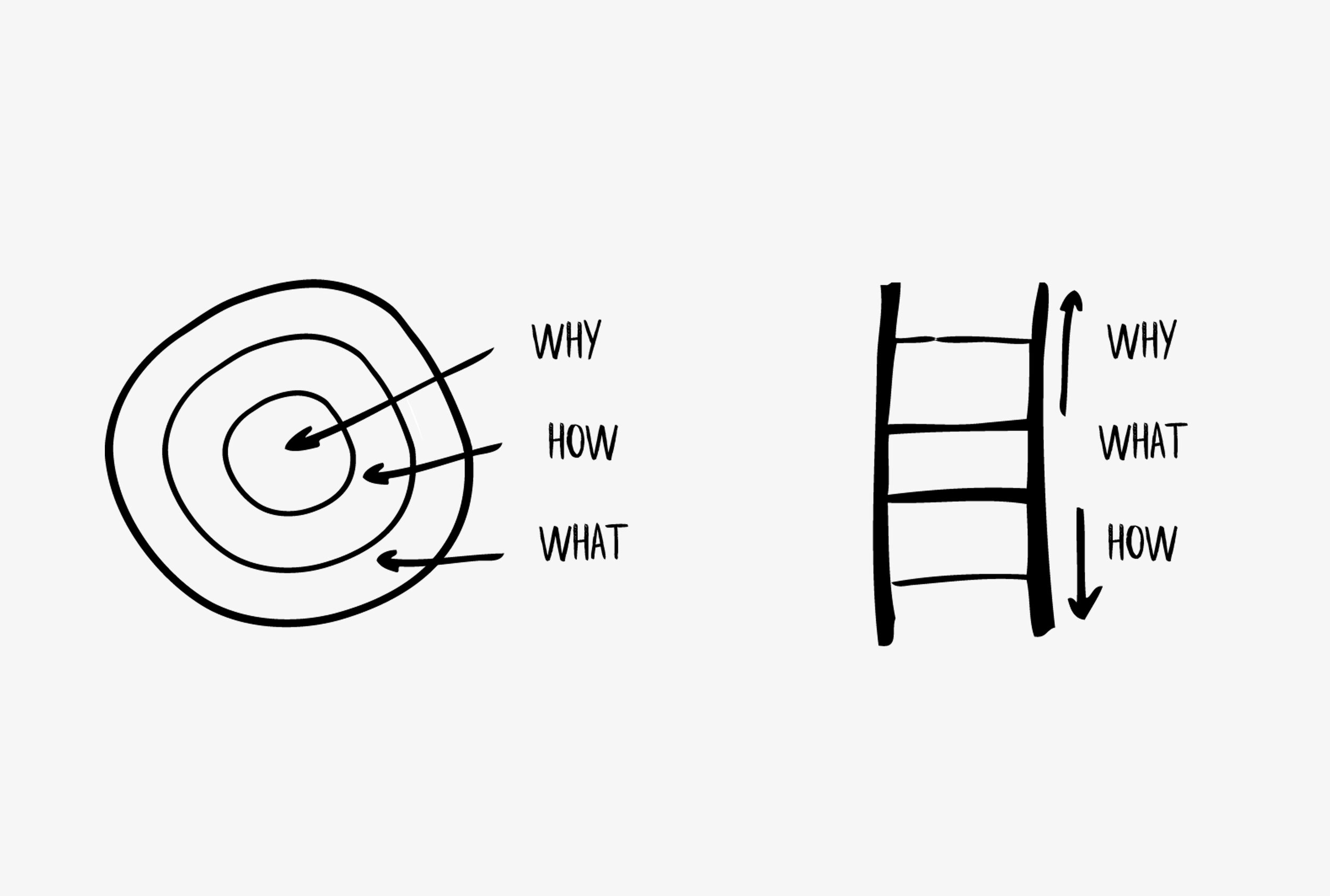

A simple set of diagrams can create an interface to open up the conversation between why, how, and what we are creating. Two models are below.

Sinek/Nietzsche/Frankel on the left, Hayakawa on the right

The result of drawing this conversation can be deeper agreements and clearer goals. Having this conversation can create more energy to move forward on what we’re going to do, together. HOW you draw this conversation will have an impact on the direction you take.

——

So…let’s take a quick step back… If you want to read more about goals, I’ve written about why vs how in the context of personal reflection and resolutions here. This essay is an excerpt from my recent book Good Talk, How to Design Conversations that matter. You can get a sample chapter and the main tool discussed as a template here.

——

Why Else? A Web of Why, What, and How

If I have my why and you have yours, then what? If these goals are not perfectly aligned, friction can develop. If you stay laser-focused on your why and your conversation partners do the same, how can you avoid becoming like the Zax, stuck with no way forward? How can we find shared goals?

Above, on the left, is Sinek’s “Golden Circle,” showing how a central why can drive a diverse array of what. People rarely have singular, one-dimensional goals, just as people aren’t one-dimensional. We’re all pulled in many directions, with layers to our needs and goals. This truth can provide a way forward: in those layers, we can sometimes find a higher why that can contain all of our individual goals or an opening to connect. We can visualize those layers using a diagram called an abstraction ladder, sketched above, on the right. Abstraction Laddering is a concept that has been around since at least the late 40s, with some people attributing it’s formalization to S.I. Hayakawa’s 1949 work, Language in Thought and Action.

Why? Why Else?

Asking simple questions like, “Why else?” can open up the conversation and unpack higher goals. Why do we want what we want, in order to accomplish what? Similarly, we can delve into how someone imagines they can accomplish these goals. Knowing the layers to our own and someone else’s goals in a conversation can help us find common ground.

Abstracting Goals

Abstraction laddering gives a different interface for the conversation between why, what and how. Instead of placing why at the center, it puts what at the center. Most of the time we come together to talk about something, not some why. Why and how, abstract and concrete goals, are placed at the top and the bottom of the ladder, in dynamic tension.

The International Center for Studies in Creativity has a wonderfully hokey video that dramatizes an abstraction laddering conversation. Roger and Suzanne are talking about Roger’s business challenges. He has a ladder company that he wants to market better to increase sales.

“Why?” Suzanne asks. Roger replies with the simple goal: in order to make more money.

“Why else?” She probes. Roger admits he also wants more brand recognition. Suzanne is developing a web of whys motivating Roger. She then moves Roger up the ladder of abstraction by asking:

“Why do you want to make more money? In order to accomplish what? Why do you want to have more brand recognition?”

Understanding and mapping all of Roger’s whys, and the whys behind those whys, can offer a richer understanding of the initial challenge. Every person has a web of whys and hows. It’s worth exploring that web if you want to work together.

Simultaneous Turns: An Interface for Goals

The Abstraction Laddering template on the below is based on a version I learned in 2015, when I took a Design Thinking Instructor certification course with the LUMA Institute. Drawing this template as a large poster creates a visual and durable (ie, sticky) interface for an important conversation on where we want to go together—finding our shared goals.

The interface breaks down the complexity of the conversation into clear turns that each person can take at the same time. This tool is also a handy method for reframing issues as opportunities. Set aside 30 minutes to try it. It might help you redesign an important conversation that matters.

What: Start with writing your current challenge in the middle of the paper. (We start with “what,” not “why.”) This is our initial goal.

Why: Give everyone some time to think on their own. Using 3 x 3 inch sticky notes, have everyone write 2-3 reasons (one per sticky note) on why they feel this challenge is critical. I ask them to finish the phrase “In order to…”

Invite people to post the “why” sticky notes and map them according to their level of abstraction, clustering similar goals.

How: In what ways might we achieve these goals mapped in step 3 or the initial goal? Ask people to get concrete with their goals by finishing the phrase, “We could…” with each person writing 2-3 “hows.”

Post up the “how” sticky notes and map them according to their level of concreteness, clustering similar approaches.

Steps 1-5 help us map a web of whys and hows. How can we find a way forward and close out this conversation? Giving each person 2-3 sticky dot votes to choose their favorite why and how can give us a “heat map” of where there’s shared energy and close out the conversation. Now we can talk about how to move forward.

Download a version of this diagram as a step-by-step worksheet here.

Frame your questions better with Abstraction Laddering

My favorite go-to way to use abstraction laddering enforces the “Think Alone, Think Together” principle and helps me get a snapshot of where a team is on a challenge.

How might I get in Shape?

Using the question of how to get in shape as an example, I ask participants to write down 3 reasons WHY they have wanted to get in shape and 3 approaches to HOW to get into better shape. I then invite them to cluster their whys and hows, having a visual dialogue on what level of the question to address.

Let’s Break it down:

Some common reasons Why people want to get into better shape:

Have more energy

keep up with their kids

Feel better about themselves

Fit into their clothes.

Each of these reasons why are more “abstract” goals. And we can make them more abstract by asking why again and again:

Why do I want to have more energy? Because it feels good!

Why do I want to feel good? Well…that’s where the questioning ends! The answer is “Because!”

But *How* to have more energy? There’s a lot of ways to get there: Sleep better, eat better…

How do I eat better? Go Paleo or Raw Vegan!? Get Blue Apron instead of takeout?

Doing this as a brainstorm online can look like this:

Getting clear on what “level” of question we’re addressing can take a thorny question and make it more specific, more solvable. I’ll give a more real example: Do we go after our core customer or try to get a new demographic? Can we do both?

This question came up during a 2-day problem framing workshop I ran recently for a major fashion brand (I’ve blurred out an identifying sticky note) It was a thorny question, and a quick Abstraction Laddering exercise helped the team begin to unpack different approaches to this issue.

The right question is always about finding the dynamic tension between the giant, abstract goals (notice the $$ at the top of the diagram?) and the nitty gritty approaches to the problem. How far into the weeds are we going? Is this meeting about giant goals or detailed actions?

Getting clear on the “real” why behind the why can help teams solve the right problem.

Getting clear on all the approaches open to us (the hows) helps teams solve the problem in the right way.