I believe that psychological safety is essential for groups and organizations to do their best work. And I’m not alone. Google has studied it, books have been written about it. Even little old me has written about it. In my men’s work we talk about creating safety for ourselves first, so we can do it for others. And I stand by that point of view.

I also stand by the work on safety I did with a wonderful group of Sprint Leaders at Google Relay, which explored the future of the Design Sprint for its 10-year anniversary. Working with the Google Sprint team for the last several years has been one of the highlights of my career. Every time we collaborate, they push me to go deeper and find something more real, honest and true in my work. This time was no different.

My team designed a "safety manual" with some amazing resources (including one of my recent favorites: Dr. Lesley Ann Noel’s Positionality Wheel – a powerful way to build safety through acknowledging diversity)

But what if it’s actually impossible to create safety?

Protection over Safety

I recently had the pleasure to interview Tyson Yunkaporta, author of Sand Talk: How Indigenous Thinking can Save the World.

He captures a fundamental, and fundamentally different perspective on safety that I think is essential to share:

“The biggest problem with contemporary approaches is to risk the illusion of safety as a human right that can be controlled as a variable in advance - it cannot.

In fact there is no such thing as safety in Aboriginal worldviews. We have no word for it in our languages. Safety provided by an invisible hierarchy is complete anathema to our way of being. There is no agency in safety, which places a person in a passive role at the mercy of authorities who may or may not intervene when needed. So we have no word for safety or risk...

however we have plenty of words for protection.

Protection has two protocols:

The first is to look out for yourself.

The second is to look out for the people around you.

This is such a wonderful way to live: knowing that you have the power to defend yourself and the ones you love while also being intensely aware that at any given moment there are dozens of people who are watching your back as you watch theirs.

This is the interdependence that our kinship pairs and network of pairs offer.”

Protocols of Protection

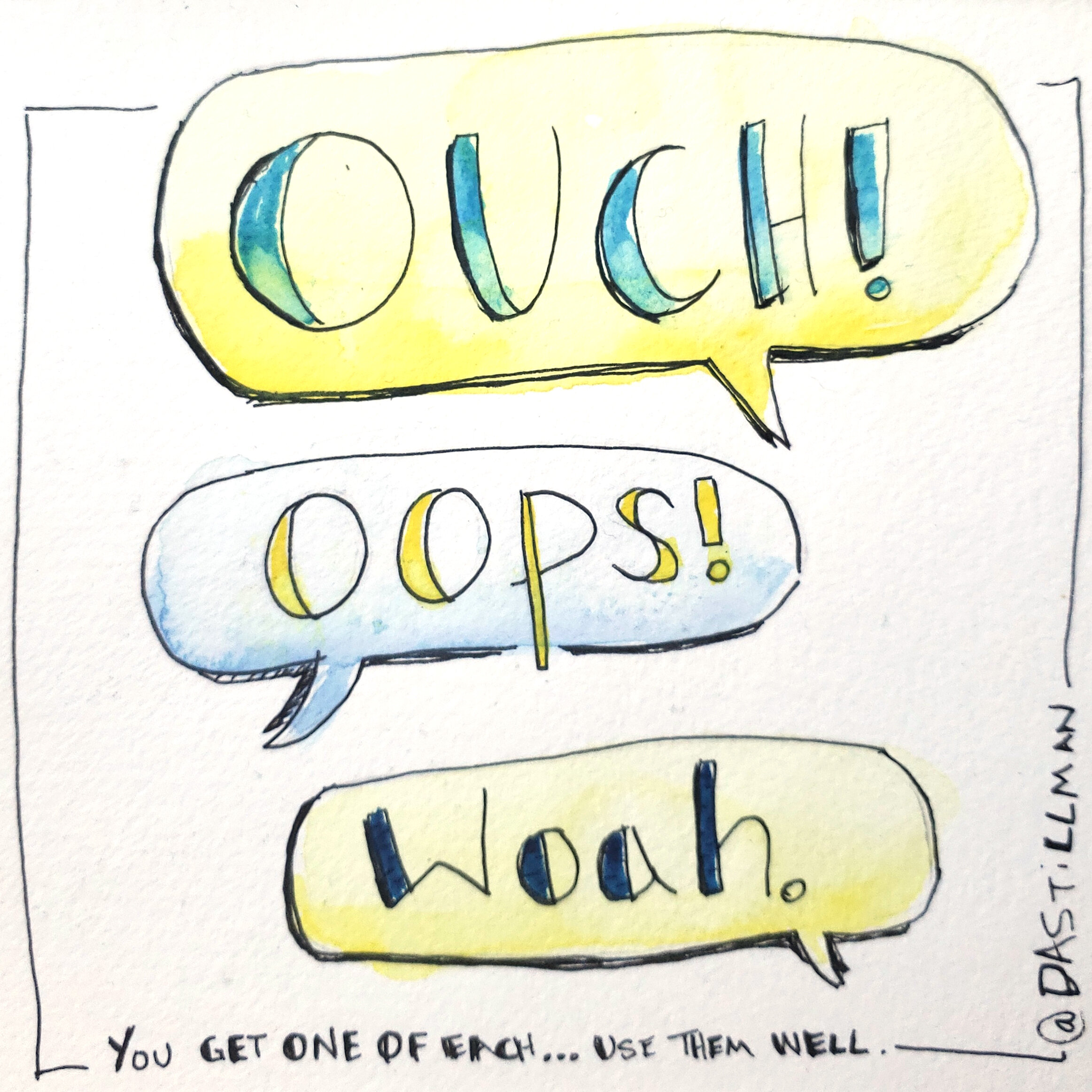

Last year, Annaliese Griffin interviewed me about designing for error and repair in conversations. In passing, she mentioned a framework she had recently learned in a parenting and racial equity workshop: ouch, oops & woah.

Annaliese summarized this protocol like so:

If you say something that comes out wrong, that you suddenly realize is kind of shitty, or just sounds different hanging in the air than it did in your head, you say “oops.”

If someone else says something that hits you in a way that feels bad, you say “ouch.”

If the conversation is moving too fast, you’re not following a line of reasoning, you aren’t familiar with a concept or an acronym, or you just want to slow down, you say “whoa,” and ask for clarification.

The point of this tool is to signal a clear set of values: Mistakes are normal, harm can be mended, it’s okay to not know something, and accountability is a shared responsibility.

In our conversation, she also added (and I think this is essential) that you can say “oops” if someone says “ouch” or “woah”…that is, if you say something off, you can take a mulligan.

Seed it before you need it

It’s SO important to set up these protocols of protection before the conversation really gets underway. It’s not a question of if, it’s a question of when someone will trip up and say something off. As the Avenue Q song goes, everyone is a little bit racist (even by accident!). We all have phrases we still use that we shouldn’t. For example(s):

I reminded someone recently (and nicely!) that their use of Pow Wow was a no-no. They thanked me and told me that they are always learning how to clean up their language. They then related how their company recently stopped using “brown bag” for their lunch-and-learn sessions because the people of color in the organization asked them to stop.

This is not about “cancel culture” or “tiptoeing” around. It’s about people being upfront about when they feel harmed so the harm can stop...at least, in that specific instance!

Hopefully, we can all share an attitude of learning and moving forward, together. This is the spirit of Ouch, Oops and Woah.

So, put the protocols in place before you need them. Plant the seed of mutual protection early, so that it’s a shared effort to create a safe space through bravery.

Safety is impossible, so design a protocol for people to protect themselves and each other instead.

Error and Repair

In my book, Good Talk: How to Design Conversations that Matter, I identified Error and Repair as a key element in the design of conversations, of all shapes and sizes. So, if “oops” isn’t enough, you might need these handy, science-backed instructions for how to say you’re sorry.

How to Say “Sorry” in Four Easy Steps

If you have caused someone offense, and you’d like to repair the relationship, an apology is in order. The Greater Good in Action (GGIA) project works to synthesize the best science on how to live a good life. GGIA cites a delightful study titled “An Exploration of the Structure of Effective Apologies” outlined here:

1. Acknowledge the offense. “I made a mistake” is much more effective than “mistakes were made.” Be specific.

2. Provide an explanation. Backstory or context can help, but making an excuse or minimizing the harm another person feels will backfire. If you want to hear the formula in action, there’s a lovely podcast episode from the GGIA here.

3. Express remorse. You might feel bad for hurting another person; sharing that remorse can help build empathy.

4. Make amends. Don’t stop with feeling sorry. Offer to do something about the mess you’ve made. That’s the essence of repairing the error. Ask what might make them feel better rather than assuming you know. Make the offer specific and tangible.

The study showed that the acknowledgment of responsibility (#1) and an offer of repair (#4) were the most important elements. A word of caution: Don’t try to fake an apology, even with this guide!

Recently, someone pointed out that this process is very similar to Ho'oponopono, an ancient Hawaiian spiritual practice that involves:

“learning to heal all things by accepting "Total Responsibility" for everything that surrounds us – confession, repentance, and reconciliation.”

For your teams, for your organization, for your family - establish protocols of protection. Watch each other’s backs, and speak up when you see or feel harm. Then...allow someone to apologize and offer forgiveness if you can - which is much harder than apologizing.